|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

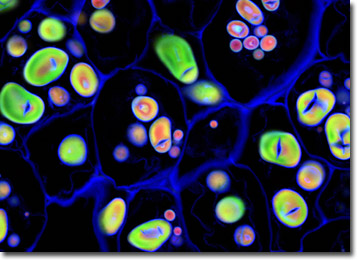

Confocal Microscopy Image Gallery

Plant Tissue Autofluorescence Gallery

Potato Tuber

Today potatoes are commonly eaten mashed, fried, boiled, baked, and most any other way imaginable, but when Europeans first came into contact with the potato plant (Solanum tuberosum) they were very skeptical of it. A native of South America, the potato had been cultivated for well over a thousand years by the Incas when Spaniards arrived on the continent in the mid-sixteenth century and returned to Europe with specimens of the plant.

Though grown in this new home as a curiosity, Europeans quickly recognized the plantís similarities to the poisonous nightshades and were at first uninterested in consuming any of its parts. Eventually, however, it was discovered that the potato tuber, an enlarged end of one of the plantís undergrounds stems, was both edible and nutritious, and by the dawn of the eighteenth century the potato tuber had become a staple of the Irish diet, though its use as a vegetable was much slower to catch on in France and many other countries.

Potato plants form tubers as a site to store starch for gradual use during the winter months when photosynthesis often cannot be carried out. Each plant generally develops several of the special food reserves, some retaining twenty tubers or more at a single time. The tubers vary somewhat in size, shape, color, and texture, and there are more than 500 different varieties currently cultivated. Since new potato plants can be grown from a piece of tuber that contains one or more buds (more commonly referred to as the eyes of a potato) that will be identical to the plant from which the parent tuber was produced, maintaining desirable characteristics in the plants is a simple process. However, this practice of vegetative reproduction has important drawbacks. Most notable, crops comprised of potatoes that are all genetically identical can easily be destroyed by insects or disease because the plants are all susceptible to the same pests, viruses, bacteria, and fungi.

Contributing Authors

Nathan S. Claxton, Shannon H. Neaves, and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.